Mattie Hammond in 1889 at age 17.

Mattie Hammond found grace in the everyday happenings of life — a lively family dinner, a maple tree turning golden in the autumn, a child’s gift of a blue jay feather— and recorded those moments in poetry. During the course of her 90 years, Hammond wrote at least 60 poems, many of them later in life. Her five children received them as gifts, enjoyed them and then tucked them away with other family mementoes.

The younger generations of Hammond’s family did not know about her poetry until Burton Clark, one of Mattie’s great grandsons, discovered a few poems 18 years after her death. Over the years, Clark collected her poems from family members, eventually assembling 60 poems into a book, titled "A Feather," scheduled to be published this summer.

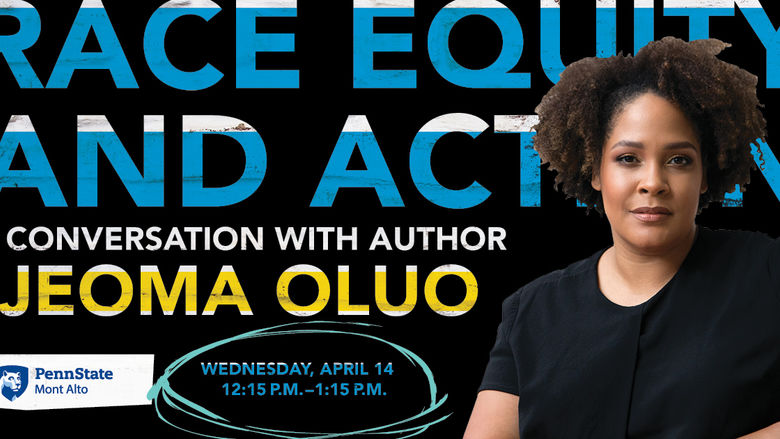

Clark, who lives in Emmitsburg, Maryland, enlisted his friend Nancy Funk, assistant professor of integrative arts at Penn State on the Mont Alto campus, to write the foreword to the book. Reading Hammond’s poems inspired Funk to write a play based on her life. When the COVID-19 virus disrupted plans for the play’s performance this spring, Funk transformed the work into a radio play, which was read by Mont Alto faculty and staff, along with the Trinity Players of Waynesboro, and recorded on Zoom and alter shared on Mont Alto’s YouTube channel.

“Mattie did not have an easy life, but she took such joy in the little things. She experienced a lot of tragedy, yet she could write such beautiful poetry,” Funk said. She was also struck by how late in life Hammond composed many of the poems. In her foreword to "A Feather," Funk wrote, “Just as Grandma Moses painted people and scenes she knew best, so this great grandmother poeticized the days she experienced.”

Mattie Elizabeth Gale was born in West Tuckerton, New Jersey, in 1872 and spent most of her life in that state. She married her childhood sweetheart Mitch Hammond, but he died at the age of 44, leaving her with five children to raise. Around 1930, as the Great Depression was beginning, fire damaged her house in Camden. She worked as both a midwife and a clerk at a dime store to support her family. In World War II, she lost a grandson, Robert “Bobby” Hammond, when his destroyer, the USS Warrington, sank off the Bahamas in a 1944 hurricane.

With six grandchildren and nine great grandchildren, her life revolved around family. When she died at age 90 in 1962, she was living in Bloomfield, New Jersey, with her youngest daughter, Pat.

Funk’s play begins with Hammond dozing in a rocking chair on the eve of her 90th birthday, looking back over her life. Each scene of remembrance is bracketed by two of her poems, and includes her wedding day, the death of her husband, the fire at her home in Camden, the loss of Bobby in World War II and finally, her last birthday party.

Some dramatic license had to be taken with the play, Funk said. For example, Mitch died of pneumonia, but Funk added that he was working in a munition factory on the eve of World War II when he fell ill. Clark said the family did not have difficulties with the additions. “After all, it is a play,” he said. “There are some things we really didn’t know a lot about, such as her wedding, so Nancy had to improvise some of the details.”

Clark met Funk while both were working at the National Fire Academy in Emmitsburg, where he held the position of department director of management science and Funk was working as a contractor teaching communications classes. The two became friends, drawn together by their love of writing. Clark, who had worked as a firefighter in Washington, D.C., and a volunteer firefighter in Prince Georges County in Maryland before retiring from the academy in 2014, wrote a book about his experiences, "If I Can’t Save You, I’ll Die Trying."

Funk had been writing plays for years, so it was second nature for her to take on Hammond as a subject. She had just won a competition in Hagerstown, Maryland, with her play “Sisters of the Locker Room,” about a group of bored senior citizen women at a local YWCA and their life stories. Clark went to see the play and told Funk, “If you can write one like that for my great grandmother, go ahead,” Funk recalled.

When Funk recast “A Feather” as a radio play, members of the Trinity Players, who were going to put on the original play, agreed to participate, as did a number of Mont Alto faculty and staff. Clark volunteered as the narrator and Deb Hollen, one of Funk’s students from when she started teaching at Mont Alto in 1976, read the poems in the character of Mattie. “We really didn’t have time to rehearse. We did one reading and then recorded it,” Funk said. “Everything considered, I think it came out well.” A live theatrical performance is planned for the next year.

Both the play and the book bear the title “A Feather,” a poem Clark discovered was about himself:

Great grandson brought a feather

From a blue jay wing today,

I do not know why the blue jay

Threw that one away

Maybe just as a token gift

To a little boy

Who on a lovely summer day

does not play with toys…

“I spent much of my childhood with her. When I read her poems, I can hear her voice again. Finding this poem and reading it was very emotional for me,” Clark said. In 2001, Clark had his own Mattie moment when his 8-year-old grandson, Golden, gave him a blue jay feather. “I was able to hold back my tears until he ran off to play,” Clark said. “That blue jay feather was magic.” He put the feather away for safe keeping.

In 2004, when Clark’s great-aunt Pat died at the age of 101, “Mom gave me a plastic case, and said that Aunt Pat told her to give the case to me,” Clark said. “When I opened the case, there was a book with all of Mattie’s original handwritten poems. As I flipped through the pages, I came across the poem ‘A Feather,’ the one she had written about me.”

The blue jay feather he had given her was there, pressed between the pages.